The great Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges once argued in his essay “The Art of Telling Stories” that there are very few tales humanity returns to:

- the story of a warring man

- one of an exiled man who encounters wonders at sea

- and the God who was a man or a man who thought himself a god.

I kept thinking of Borges as I read The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin, a celebrated Chinese hard science fiction writer best known for his trilogy Remembrance of Earth’s Past. Why Borges while reading Cixin, you may ask?

Because The Three-Body Problem is another retelling of H.G. Well’s War of the Worlds. I would argue, and perhaps this is too bold a claim at my young and tender age, that there are essentially a certain number of science fiction plots that are retold, most of which fall into the categories Borges observed:

- Man wars (with an alien race)

- Man explores (the seas of space)

- Man creates (machines, Gods, etc)

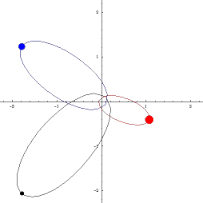

Now that my literary theory rambling is done- let’s chat about the book. The plot- humans finally get in touch with an alien race- the Trilsolarans, who inhabit a world surrounded by three planetary bodies (which means a lot of uncertainty and chaos). The Trisolarans, once they discover how stable earth is, set sail to destroy the human race. Of course, these are the macro movements of the novel. On the micro scale, the story follows Wang and Ye, two scientists who represents the opposing forces- Ye wants the aliens to invade and Wang is our salvation.

The novel begins with the Cultural Revolution in China and Ye’s involvement and family tragedy and fast-forwards to our time to describe Wang’s research and his discovery of a game called Three-Body. The Three-Body game, it turns out, is a representation of the Trisolaran planet. The Human Traitors use it to profile people that might fit their criteria to join their mutinous cause.

Though I found the parts about the Cultural Revolution to be beautiful and sad, I found the game portions to be dry and gimmicky. Perhaps it was that on the Trisolaran planet (represented in the game), people die frequently because of the instability of the three planetary bodies, preventing the reader to form an attachment to any one character. Or perhaps the scientific explanation that are key components of those parts of the novel were long and dry. While it is clear that Cixin knows his science, he fails at times to mask it well like Asimov, whose writing never struck me as overly technical.

Despite the dryness and contrived portions of the novel, I found that those parts do not undermine the overall beauty of it. The story of Ye and her family’s trials and her hatred for humanity certainly stand as the most moving and real parts of the novel, and it is that character that makes me want to finish the trilogy, not the story of the Trisolarans.

And so I am left with the keen desire to pick up The War of The Worlds and analyze the plot that Wells once used. Borges was right- we wrap the same plots in different ways- and that is the beauty of literature.

Borges argues at the end of the essay that novels must evoke the epic (in the classic poetic way), and that is what most resonates in Cixin’s novel: the moments where humanity seems to still have hope despite the impending war with the Trisolarans.

There are moments of such poetic beauty, e.g. when the aliens send humans a message: “You are bugs.” A police officer character takes Wang to a field of locusts and says that despite humanity’s efforts at eradicating the bugs, they have survived and that the war against bugs is still uncertain. It is always a question of poetic beauty in these grand-scale books.

Overall, Cixin’s novel is great if dry at times. His moments of poetry are truly a feast for the imagination. I will return to him only after contemplating the three plots of science fiction. There is much to be learned from Borges, alien invasions, and Chinese science fiction.